| |

| |

|

The Duncan Sisiters |

| (Rosetta

and Vivian Duncan) |

| Topsy

and Eva Play Vaudeville |

| By John

Sullivan |

|

|

|

|

|

|

In 1923 Topsy and Eva first

wandered on the stage in a musical comedy, brought there by two

vaudevillians in their early twenties, Rosetta and Vivian Duncan. By 1927,

as they were preparing for the silent movie version of their "travesty" of

Uncle Tom's Cabin, Rosetta claimed that they had already played the roles

1872 times, four years worth of nine performances a week. After 1927 there

would many more. Topsy and Eva became part of their vaudeville act. They

revived the play twice in the Thirties. At the end of that decade they

appeared in their now familiar roles on television in one of the first

musical comedies produced there. In 1942 they were back on the boards as

Topsy and Eva again. Their work as a team would end with Rosetta's death in

1959. At the time they were playing at Mangam's Chateau outside of Chicago

in an act built around nostalgia for vaudeville. |

|

It may well be impossible

to make complete sense out of the nonsense Rosetta and Vivian brought to

generations of audiences given the documentary fragments left to tell the

story. Still, enough can be pieced together using reviews, records, sheet

music, film, playbills and the few articles about their work that remain to

make a preliminary map. Like all early maps what follows may prove in time

to have fanciful figures on the fringe and to get proportions out of size.

It at least will provide yet another piece of evidence about what happened

to Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin in the twentieth century. |

|

|

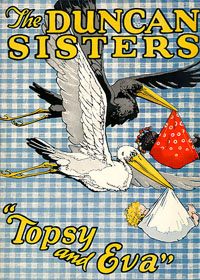

Promotional Postcard - Topsy & Eva |

|

|

Topsy and Eva Reborn

Very few, if any, of the

thousands who brought Uncle Tom's Cabin to the stage did so to promote

Stowe's message. When the Duncans discovered the possibilities of using the

novel to expand their own career, surely they had neither the proper role

for Christians nor the horrors of slavery in mind. The stories they told

about how they became Topsy and Eva are all tempered by the fact that they

appeared in response to press interviews. The most broadly distributed

version appeared in The American Magazine in August, 1925. The sisters were

established vaudeville stars by that time. "A little more than two years

ago," Rosetta told an interviewer, "a man came to us to see about doing

something in motion pictures." After several ideas were broached and

dismissed, "finally he said . . . 'I guess we'll have to black you up.'"

"We'll do Uncle Tom's Cabin," Rosetta recalled exclaiming, "but we'll make

Topsy and Eva the central figures, instead of Uncle Tom." In this version of

the story the sisters were at a public library within an hour checking out

an old copy of the book. They put the film project on hold and began to work

on what they knew best, a mix of vaudeville and musical comedy. "Our manager

got Catherine Chisom Cutting [sic] to write the book for our plan." The

Duncans did the music. The show opened "four weeks later" in San Francisco. |

|

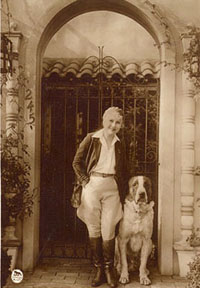

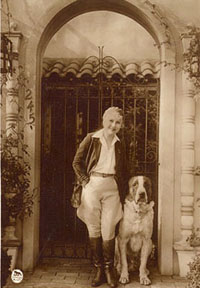

Publicity Photo from

The San Francisco Examiner (1923) |

|

|

That interview suggests

that the Duncans knew something about Uncle Tom's Cabin, enough to see the

possibilities Topsy and Eva provided the pair. What they produced, however,

indicates that they knew the symbols, but not what Stowe crafted them to

stand for. For vaudevillians the word association game prompted by "I guess

we'll have to black you up" surely linked the sisters to a world they knew

well. The long tradition of blacking up would last for much of their career.

In the Twenties their relatives would be named Jolson, Cantor, Moran and

Mack, Gosden and Correll.

When Rosetta again told the origin story during a 1931 revival of Topsy and

Eva in Los Angeles, the shifts were subtle but meaningful. Now the tale ran

that the sisters were clowning around with their manager at their summer

home in Manhattan Beach when "a crazy stunt" prompted him to shout "You

ought to be Topsy and Eva." As in the earlier version, a musical quickly won

out over a movie. This time, as Rosetta told it, she "bought an old copy of

the play manuscript of Uncle Tom's Cabin from the Redondo Public Library."

Her three dollar investment proved to be a wise one. "All through the script

it kept saying |

|

'music here' 'chorus

here,'" Rosetta recalled. The transition from a Tom Show to Topsy and Eva is

a more likely one than from the book itself. Here was a routine which

would change forever the lives of "The Song and Patter Kids." It would also

affect the telling of Stowe's story.

The Romper Team |

|

At five feet two and under

120 pounds, the Duncans came prepared to play Topsy and Eva. Part of the

business they used was already in their routine. They were twelve and

fourteen when they first hit the boards at the Pantages in Los Angeles in

1914. By the time they became Topsy and Eva, vaudeville had been their life

for nine years. Starting as a small-time act on a small-time vaudeville

circuit in the west, they moved to the midwest joining the "Revue de Vogue"

where they played cheap houses in Illinois, Wisconsin and Iowa. Finally with

the help of a third sister, Evelyn, they made their way to New York and to

the stage at Coney Island. From there they moved to the Hotel Martinique in

one of Gus Edward's kiddie reviews and then on to a small role singing "I'm

So Glad My Momma Don't Know Where I'm At" in Doing Our Bit at the Winter

Garden in 1919. In Fred Dillingham's She's A Good Fellow (1918), they were

"the terrible infants of the boarding school." Tip Top (1920) found them

cast as two sisters named "Bad" and "Worse." Looking younger and acting

older, the Duncans frequently appeared in "short frocks and half length

hose" in a routine featuring childish voices, close harmony and plenty of

mischief. Theirs was an "original act," they claimed, drawn from things done

as children, things natural to them, things they loved to do, and they loved

to laugh and make others do so too. Even after their early success with

Topsy and Eva, Variety called them a perenial romper team. "The sisters know

their baby stuff to and from Babyville," a reporter noted after a

turn at the Palace in 1927. Rosetta had |

| |

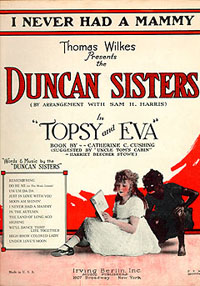

Sheet Music | "War

Edition"

(© 1918 by Leo Feist) |

|

| part

of Topsy within her even then. Vivian brought a sense of coyness and a

willingness to support mischief as the team's ingenue. The Duncans indeed

had thought of "baby stuff" as a route to musical fame before Topsy and Eva

hit the boards. Before blackface they had been working on a show to be

called "The Heavenly Twins," a story about "two orphans in a home." From it

came the signature song for Topsy and Eva -- "Rememb'ring." |

|

Sheet Music

(© 1920 by Leo Feist) |

|

|

Fragments of their

vaudeville act remain in newspaper accounts and in rare interviews. It

seemed to feature slapstick, close harmony and comedy songs plus a

sprinkling of satire. What ever it was that they did, joking around while

singing "She Fell On Her Credenza" or tossing vegetables into the audience

or mocking current musical stars, it worked. While performing in England in

the early Twenties, they met the Prince of Wales and soon were harmonizing

with him on the party circuit. They even taught him to do "The Chicago." On

stage there their usual high jinks drew audiences. Their "out of the mouths

of babes" antics were typified when the Queen of Spain appeared one evening

in the Royal Box. Rosetta came on stage with a skinned knee and immediately

went to the side of the stage where the Queen sat "and did what any child

would do," she pointed to her knee and said: "I skinned my knee Princess

Mary! Can you see my skinned knee?" So much for decorum, the audience

howled. The skinned knee bit had been part of t he routine

from the days of Tip Top. Rosetta and Topsy were already |

|

sisters in spirit. That was

the Duncan's act, an innocent imp harmonizing with a pretty blond little

sister who behaved like an unchurched Eva. Topsy and Eva would provide them

a vehicle which would allow for old routines in new costumes coupled with

fresh possibilities to be developed. Their presence, their style, both had

been established before what would become years in burnt cork.

Uncle Tom's Cabin In A

Fun House Mirror |

|

The Duncan Sisters' Topsy

and Eva first premiered at the Alcazar in San Francisco in July, 1923. It

would remain there eighteen weeks, though for the final two, because of a

dispute between the Duncans and producer Thomas Wilkes, the White Sisters

took over the lead roles. Despite talk of an immediate move to New York

following the run and rumors of producers including Ziegfeld trying to place

the Duncans under contract, the show shifted to Los Angeles for a month. The

Whites took the lead for the first two weeks. The Duncans, having settled

their contract dispute, returned to the show for the final two weeks. The

much vaunted next stop in New York, however, would be delayed. Sam Harris

had a hit on his hands there in the same theatre where Topsy and Eva was to

be staged. So it was Chicago instead for the sisters, a way stop which would

postpone an East Coast appearance for almost a year. |

|

What audiences in America

and England would see for the decade of the Twenties and again in the

Thirties and finally the Forties "just growed" in San Francisco and at every

stop along the way. Before post-modernism the Duncans had learned to violate

form and to commercialize a classic. The book by Catherine Cushing left no

room for tragedy. "Topsy and Eva is abreast of the times," Los Angeles

columnist Grace Kingsley wrote on December 9, 1923. The "old revue," she

argued, "seems to be dying a slow death through starvation." Even Ziegfeld's

Follies was "in poor health." "Nowadays shows . . . with a story are the

ones that are going over and lasting," Rosetta told her. But what a story as

the Duncans told it! In San Francisco the production opened with a cast of

sixty, a featured dancer, Harriet Hoctor, an opera star, Basil Ruysdael, as

Uncle Tom, a host of pickaninnies, and a male quartet. Uncle Tom's Cabin

became a musical comedy, bewildering some critics and delighting audiences.

Upon seeing an early San Francisco performance, Variety's critic labelled it

"a musicalized version of Uncle Tom's Cabin' with plenty of liberties

taken." Liberties indeed: there would be no whipping of Uncle Tom by Simon

Legree, no death of Little Eva, or any other "sad or tear-inspiring

situation." |

|

|

Eliza crossed the ice only

during the West Coast shake down. There never were any bloodhounds. The

sisters tried a little of everything as the show developed. Scottish aires

like "Ben Bolt" were replaced by a song which would become a permanent

fixture in the show, "I Never Had A Mammy." St. Claire married Mrs. Shelby;

Topsy made Legree wish Stowe had never made him a character in the novel and

Aunt Ophlia even learned how to flirt. "It's an operatic Uncle Tom's

Cabin,'" Tom Nunan told readers of The San Francisco Examiner, "with the

story turned into fantastic vaudeville." Throughout the Twenties friends and

foes alike would use the word "travesty" to describe the production. By the

time the show reached Chicago for a Christmas season opening in 1923, the

show's format had been well established. Harriet Hoctor's "The Bird's Dance"

would draw rave reviews. Eliza crossed the ice only during the West Coast

shake down. There never were any bloodhounds. The sisters tried a little of

everything as the show developed. Scottish aires like "Ben Bolt" were

replaced by a song which would become a permanent fixture in the show, "I

Never Had A Mammy." St. Claire married Mrs. Shelby; Topsy made Legree wish

Stowe had never made him a character in the novel and Aunt Ophlia even

learned how to flirt. "It's an operatic Uncle Tom's Cabin,'" Tom Nunan told

readers of The San Francisco Examiner, "with the story turned into fantastic

vaudeville." Throughout the Twenties friends and foes alike would use the

word "travesty" to describe the production. By the time the show reached

Chicago for a Christmas season opening in 1923, the show's format had been

well established. Harriet Hoctor's "The Bird's Dance" would draw rave

reviews. |

|

|

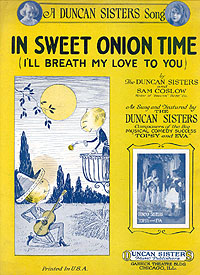

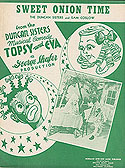

The London Palace girls,

many of whom had appeared in Tip Top with the Duncans, played the roles of

pickaninnies. The show, however, was a Duncan Sister's showcase. Rosetta

ad-libbed throughout the performance. Vaudeville bits were worked into the

plot. It is hard to imagine how "Sweet Onion Time in Bermuda" found its way

into the performance in Chicago -- except that it featured things the

Duncans could do best, and that was vaudeville. One Chicago reporter

recalled seeing the sisters toss onions into the audience during the

routine. Another, who saw a later performance of the song, described it "as

a comedy double with a funny double dance idea." "The dance," he noted, "has

the time honoured business of kicking each other in the posterior, Topsy

losing the duel and hanging a crepe on her rear." A 1920s recording of

"Sweet Onion Time" provides a glimpse of what the sisters could do vocally.

Edward Wagenknecht called it a burlesque of sentimentality.

Whenever they appeared the

Duncan Sisters appropriated Stowe's characters and brought them up to date.

One of the more tantalizing efforts to do so occurred on the final night of

the long Chicago run when the Duncans added an act entitled "Topsy and Eva

Fifty Years Later." Unfortunately what happened there remains to

be discovered. It is clear, however, that topicality

always |

|

intruded on the story line.

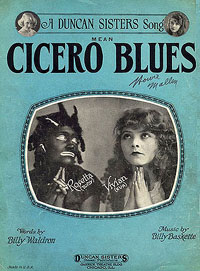

The most infamous example of the way current events found their way into the

play involved the Duncans themselves. One Sunday during the Chicago run the

sisters ventured through Cicero, Illinois, on their way back from the race

track. |

|

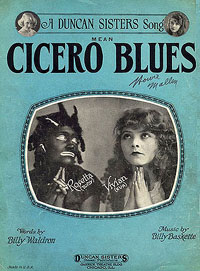

There they were stopped by

the police for a traffic violation. The result was a broken nose for

Rosetta, a traffic conviction and full press coverage. Shortly thereafter

the Duncans recorded "Mean Cicero Blues" and their publishing house made the

sheet music available. References to the incident worked their way into

Topsy and Eva and remained there during the run in New York City. When the

show shifted back to Chicago at the end of June, 1927, The Tribune noted

that the Duncans were "returning just in time to celebrate the anniversary

of their famed encounter with the comic constables of Cicero."

Certainly what the Duncans created was not Uncle Tom's Cabin. Settings and

characters were taken from the novel, but Stowe might not have recognized

them. A tragedy, a moral lesson, became a hybrid

vaudeville-variety-musical-comedy. For a time a dying medium revived a dying

text. Written descriptions of what took place when the sisters hit the

boards and publicity pictures from the press remain. The available

recordings of the show tunes give an occasional glimpse of the action. In

the dialogue you could play at the beginning of this essay, recorded as part

of a demo version of "I Never Had A Mammy" the Duncans recorded at the time

of the 1942 revival of the show, |

| |

|

| |

Cicero Blues |

|

|

the voices reveal how

dynamic the duo must have been. Ironically for a musical which took such

liberties with Stowe's text, the lines we hear in this fragment are taken

almost verbatim from the novel.

There they were stopped by

the police for a traffic violation. The result was a broken nose for

Rosetta, a traffic conviction and full press coverage. Shortly thereafter

the Duncans recorded "Mean Cicero Blues" and their publishing house made the

sheet music available. References to the incident worked their way into

Topsy and Eva and remained there during the run in New York City. When the

show shifted back to Chicago at the end of June, 1927, The Tribune noted

that the Duncans were "returning just in time to celebrate the anniversary

of their famed encounter with the comic constables of Cicero."

Certainly what the Duncans created was not Uncle Tom's Cabin. Settings and

characters were taken from the novel, but Stowe might not have recognized

them. A tragedy, a moral lesson, became a hybrid

vaudeville-variety-musical-comedy. For a time a dying medium revived a dying

text. Written descriptions of what took place when the sisters hit the

boards and publicity pictures from the press remain. The available

recordings of the show tunes give an occasional glimpse of the action. In

the dialogue you could play at the beginning of this essay, recorded as part

of a demo version of "I Never Had A Mammy" the Duncans recorded at the time

of the 1942 revival of the show, the voices reveal how dynamic the duo must

have been. Ironically for a musical which took such liberties with Stowe's

text, the lines we hear in this fragment are taken almost verbatim from the

novel.

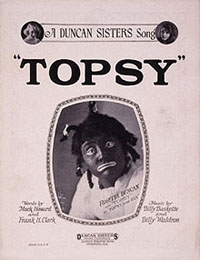

Rosetta's Topsy |

|

|

|

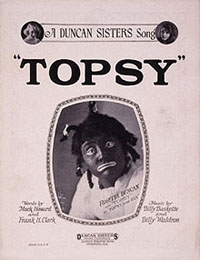

Duncan Sisters Topsy |

|

|

Before she hit the

vaudeville circuit Rosetta Duncan spent four years as the protégé of Ellen

Beach Yaw. Her sights, she claimed, were set on grand opera. She would end

up as a comedienne of the highest order, part of what Anthony Slide called

"one of the greatest sister acts on the vaudeville stage." A mimic, a clown,

a songster, adept at the ad-lib, one observer saw her as "the mistress of

about every standard hoke low comedy piece of business released in the last

decade, even Joe Jackson's mistaking the damp spot on the stage for a

quarter." She would ride the curtain to the proscenium arch in some shows.

Occasionally she took a turn at directing the orchestra. If she spotted a

bald head in the first row, one could count on her making use of it

somewhere in the performance. During the Los Angeles run in 1931 she was

known to toss her wig to a friend in the audience at the end of the final

act. Rosetta played Topsy so entertainingly that for many she personified

the character. Unlike other comediennes, she had not developed a range of

roles beyond her baby act and Topsy. She could adapt her Topsy to the times

but could not escape the character she created. Her identity as Topsy may

well be one of the reasons her career has been so sadly neglected today. |

|

As Topsy, Rosetta not only

held her own, she bettered her black faced peers, Jolson, Cantor, Moran and

Mack and Gosden and Correll at the game. Edward Wagenknecht, who saw the

Duncans perform, put it well:

Now blackface comedians are traditionally men. To give the role instead to a

young and attractive girl and then have her beat her predecessors at their

own game, marshalling six or seven times as much exuberance as any of them

were ever able to command, in all this may not seem like a very long step to

take. But it is the kind of step that makes history in the theatre.

Rosetta had studied the form and mastered it. Already a friend of Lew

Dockstader, "one of the last and one of the greatest blackface minstrels,"

Rosetta covered his appearance in The Black and White Revue for The San

Francisco Examiner in late 1923. Since we began Topsy and Eva, she told

readers, "we have been especially interested in blackface work." Dockstader

was "one of the men who created the art." "We studied every word and every

bit of his action and expression."

We have not yet found a script for the show, and even if we do we'll never

be able to recover the lines that made Rosetta the master of the ad-lib.

Whatever it was she said, her sister could never keep a straight face. Even

after the show had run for two years, Vivian confessed that "when we are on

the stage, we get to laughing about something, forget where we are in the

play, and can't pick up our cues." "I never know what Rosetta might say. . .

. It's as new to us as it is the audience." Rosetta seemed to be Topsy with

a purpose.

Vivian's Eva |

|

There is a temptation to

dwell on Rosetta's Topsy, indeed on Rosetta herself. She out-topsied the

Topsy of the novel and of the Tom Show. The character actor became both the

character and the act. Eva, however, was a far more difficult role to

undertake in a musical comedy. A second banana in vaudeville parlance,

Vivian could neither be Daddy Warbuck's Annie nor an angelic simpleton. If

Stowe's Eva sought to save Topsy's soul, in the Duncan's version of the

story Rosetta gave Eva "soul." From the first performance on it was evident

that Stowe's "sickly, saintly, going-right-to-heaven sort of Little Eva"

would not appear on stage. In her place was "a healthy, happy, romping,

somewhat mischievous girl not trying to 'save' Topsy but to become like

her." Critics recognized that Vivian could project "the last essence" of

Eva's saintliness, and did, but only in support of the comedy sure to

follow. Of course there were comedic moments for Eva but the punch lines

were always Topsys. The Duncans' Eva had a habit of faking fainting spells.

Topsy was always there to see through them and to revive her with an

asafitida charm. Vivian had to look like Eva and act like a straight man. As

Wagenknecht described her she was at once "romance and reality . . . a fairy

child and a hard headed little girl of earth." Her job was to provide the

peel for her sister's pratfalls. Strikingly when critics railed about how

the show distorted Stowe's novel, seldom, if ever, was Vivian's Eva cited as

an example.

Off stage Vivian Duncan was known as a jokester. She drove a blue Dusenberg

with needlepoint coverings, always accompanied by her Saint Bernard, parking

where she pleased and picking up tickets as quickly as she drew fans. She

was the mother of the team, selecting Rosetta's clothes and handling most of

the personal interviews. One suspects that Topsy may have come naturally for

Rosetta; for Vivian, Eva was a role to play.

Topsy and Eva and the

Theatre Critics

Lack of fidelity with Stowe's novel was enough to put off many critics. How

could Topsy and Eva be based on Uncle Tom's Cabin with no whippings, no

death of "the heavenly child," no moral messages? What was one to make of it

when the opening curtain revealed "a fine group of pickanney' chorus girls"

singing "Old Folks at Home" and "Old Black Joe" with Uncle Tom in the lead?

How could it be that Eva purchased Topsy at auction for a nickel? Such

complaints would find their way into reviews in towns where more than one

theatre critic made a living.

Despite nearly 200

successful performances on the West Coast and nearly a year's stay in

Chicago (where box office receipts approached a million dollars), |

| |

|

| |

Vivians Eva |

|

|

when the show reached New

York the critic for Variety was appalled by what he saw. "Just how this

opera managed to please the prairie dwellers so long will ever remain a

conundrum hereabouts," he wrote. "Topsy and Eva is a novelty in one way," he

admitted. |

|

It is the first time any

legit producer has shown courage enough to try to sell Manhattan village a

composite burlesque under cork, and expect it to live up to a reputation

manufactured in the broad open spaces, where space and more space seem the

only answer to the cross-word puzzle of the show business." "If this one

clicks," he reported, "a tea house in the Bowery ought to clean up." In

short, for many Topsy and Eva wasn't Stowe and it wasn't legitimate theatre.

Critics who liked the Duncan's production took both the loose relationship

to the novel and the hybrid form of the play in style. "The less you know

about the real Uncle Tom,'" The Boston Globe reported in 1925, "the more you

are likely to enjoy his present reflection in a musical setting." "Not

knowing you won't regret that there is no ice for Liza to jump across while

chased by angry bloodhounds, and you |

| |

Publicity Photo (c.

1924) |

|

|

won't be surprised that

Little Eva, the 'heavenly child,' does not die to the accompaniment of slow

music and celestial visions." In a way the Duncans were both

preservationists and pioneers. Even if for purposes of publicity, during

their New York run they sponsored essay contests in the local schools on

Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin. Their creation broke all theatrical conventions.

After seeing a production in Los Angeles in 1931 a reviewer reported that

Topsy and Eva "is so completely naive that it baffles description. Coming

under no recognizable classification -- it is a farce, melodrama, music,

opera, pageantry, burlesque and dance rolled inextricably together." Could

Stowe ever have imagined a day when Simon Legree cracked his whip while the

London Palace Girls, costumed as pickaninnies, did the Charleston?

|

Travesty with a Capital

T: Topsy and Eva, the Movie |

|

|

Theatre Movie Program

(1927)

Egyptian Theatre, Los Angeles |

|

|

By the end of the Twenties

the Duncans could demand $7,500 a week plus half the gate over $25,000

weekly take on the vaudeville circuit. Vaudeville, however, danced on tired

legs. Both radio and film drew audiences and performers from one venue to

another. Increasingly vaudevillians fronted film showings. In 1927 Rosetta

and Vivian finally took Topsy and Eva to the silent screen.

From the start of the production troubles mounted. The June, 1927, Photoplay

reported "mutterings of thunder and flashes of lightning from the Topsy and

Eva set" and "hints of Greta Garbo-ish temperament from the Duncan Sisters."

"Stories of the untoward activities of Rosetta Duncan" circulated through

out the industry. She, it seems, had "her own ideas about how pictures

should be made." Before a quarter of the film was completed, production

costs were "huge." "The Duncan Sisters," Photoplay noted, "apparently got as

much fun fighting the production staff as they do in battling with traffic

cops." Directors came and went. Del Lord, who had chauffeured the Keystone

Kops through many a film, came late to the director's chair. At the last

minute D.W. Griffith was brought in to add bathos to slapstick. |

|

The film opened in

spectacular fashion at Grauman's Egyptian in Hollywood in June, 1927.

The live show before the picture lasted almost as long as the film itself.

Rosetta, who estimated that she had used a ton of cork playing Topsy to that

point, appeared in"a straight-blond wig . . . ending in a lot of round

bouncing curls." I don't want her to go blackface this time," Vivian told a

friend. On stage the Sisters sang old favourites. They mocked Aimee Semple

McPherson and brought back their burlesque of grand opera. "Any of their

songs are good," Louella Parsons reported; "it's not so much what the

Duncans sing, as the way they sing. Their comedy is unfailing." So long as

the Duncans fronted the film, it was a hit. The film by itself was not. |

|

Topsy with technology

proved to be too much. Parsons thought that Rosetta saved some of the Del

Lord slapstick scenes. Griffith, she believed, rescued "the picture from too

much horseplay." She was the kindest of critics. Title cards could not

replace the ad-lib. Harmony had no place in a silent film. All that was left

for the sisters was visual comedy. The film added a kind of cleverness too

big for the stage and its emphasis only made the movie version even less

true to Stowe's novel. When the picure opened, audiences saw a white stork

racing a Doctor to the St. Claire home and "winning out delivering Eva ahead

of him." Title cards moved the scene to two months later. Now a black stork

raised "havoc by going through rain and lightning" to deliver Topsy. Turned

away from "the homes of coloured folks," the stork dropped Topsy into a

barrel. Whenever slapstick was possible, slapstick appeared. Before being

placed on the auction block, Topsy stole Legree's chewing tobacco and bit

off a wad. Once on the block she became ill and "got rid of the cud." Near

the end of the movie Topsy escaped Legree by sliding down a fence rail on a

saddle, putting snow shoes on a horse, and riding across the ice flow.

Instead of bloodhounds, she was chased by the family's St. Bernard. She

arrived at the St. Claire's just in time to save a fortune and Eva's life.

The reviewer for The Chicago Tribune, who saw the picture in September,

1927, gave his readers a mouthful of title card. The account runs: |

| |

|

| |

Publicity Postcard

"Made in France" (c. 1930) |

|

"You got plenty of white

angels in heaven -- hab a black one! Stop twang'n on them harps an' lissen

to me! Ef ya' let L'll Missy lib Ah won' lie no mo'er. Ah won'steal no mo'er.

Ah won' do nothin no mo'! Ef yo' don' want the debbill tuh get me away from

yo' -- Yo bettah act quick! An' I won' ask yo' to make me white lak snow,

but, jes' a nice, light tan.

Topsy's prayer answered, a happy Aunt Ophlia put her in bed next to Eva and

"the pair fell asleep in an affectionate embrace."

The film Topsy and Eva was a box office failure. Vivian Duncan placed the

blame on the studio. In her opinion the director had turned "a comedy-drama"

into "a slapstick farce." "It was a sacrilege to play it as a farce," she

asserted. Variety's film critic thought that when the film hit the road

without the Duncans fronting it that "its best chance" for an audience would

be "the kiddies." It will, he argued, "be able to repeat at special kiddie

shows." |

|

Topsy and Eva as

Educators |

|

|

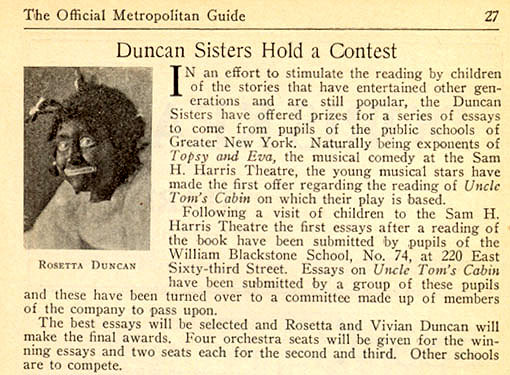

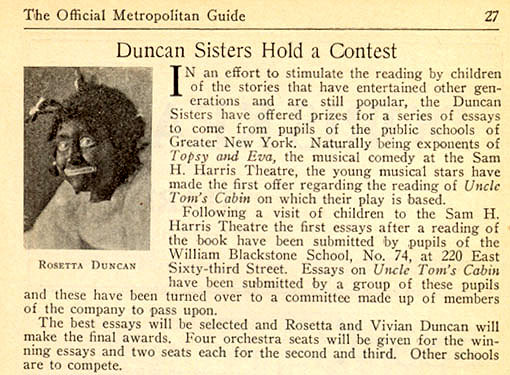

|

(New York) Metropolitan

Guide 15 March 1925 |

|

|

The Duncans, kiddie

specialists themselves, marketed Topsy and Eva to children as well as to

adults. With nine, and sometimes ten, shows a week, it often played three

afternoons as well as every evening. From the play's first performance in

San Francisco critics described the show as clean, wholesome entertainment

for youngsters. Advertisements often made children target audiences. During

their appearance on the New York stage in the mid Twenties the sisters

sponsored an essay contest for grade school students reportedly to revive

interest in American literature. Not surprisingly the first book suggested

for review was Uncle Tom's Cabin. The cast served as judges and the prize,

tickets to Topsy and Eva. When the show returned to Chicago in the late

summer of 1925, gifts were offered to children attending afternoon

performances. During the second Los Angeles run, advertisements welcomed

youngsters back stage after the performance. Advertisements for the film and

stage appearance proclaimed "Your Children Will Never Forgive You if they

don't get to see this combination." The importance of the pitch to children

ought not be overlooked simply as an advertising ploy. The show for most was

their only contact with Uncle Tom's Cabin.

A review of the stage play by The Boston Globe critic in 1925 suggests even

broader implications. The writer pointed out that while "every American" had

heard about Uncle Tom's Cabin, it was unlikely that "more than a small

percentage of the present younger generation of theatre goers in the large

cities of the country have ever witnessed a performance of the play" -- let

alone read the novel. Although Tom Shows had been produced "more than

200,000 times since civil war days" for the "small towns in America," Topsy

and Eva was a show designed for metropolitan audiences, for a new generation

in a new location. It would work for those with fading memories of the past

and for those who really had no past at all when it came to Stowe's thesis.

In a way Topsy and Eva became the origin story for those who had neither

read the novel nor were aware of its aims. As the play went through revival

after revival it evoked memories of earlier productions, not of Stowe.

Nostalgia became a drawing card and the Duncans played it well. During the

third run in Los Angeles in 1931, they called on those in the audience who

had seen it in the previous decade and asked them to stand. Topsy and Eva

applauded them. Given the way the Duncans worked, the same ploy most likely

was employed during the World's Fair revival in Chicago and during the final

run in 1942. The longer the Duncans appeared as Topsy and Eva, the more its

hit song " Remembering" resonated with the show. Almost from the beginning

audiences came to see the Duncan Sisters in Topsy and Eva, not Stowe's Topsy

and Eva. In the process they came away happy with the Sister's variant of

the novel. In a sense, drawn into remembering, they left forgetting.

A Funny Thing Happened On

The Way To Interpretation |

|

|

|

Los Angeles Times

(1923) |

|

|

One ought to be cautious

when seeking meaning from the Duncan Sisters' career as Topsy and Eva. While

interpretations of Stowe's novel may have changed over time, the novel

itself did not. Topsy and Eva is another matter. All the available evidence

suggests that although the framework for the musical may not have altered

much, the content, from jokes, to songs, to dances, to cast size, went

through a variety of revisions, sometimes even in the same run. While

programs listing scenes and songs and dances in order can be found, they

give the barest of descriptions of a comedy whose success rests on Rosetta's

ad-libs as much as anything else. True, the 1927 film is extant, although

not readily available, but Vivian branded that text as a

sacrilege. The task of coaxing meaning from

their |

|

Topsy and Eva is all the

more complicated by the Duncans also assuming the roles in vaudeville

routines. What, for example, is one to make of Rosetta's appearance at the

Palace in May, 1931, on a bill headed by Ed Wynn? There in Topsy's

"blackface make-up" she sang "Zwei Herzen im Drei-Viertel Tank." She was

"impish as ever," The New York Times critic noted.

No where is the danger of

imposing an ideological set on the text the Duncans' left more evident than

in the case of the 1927 film. Much of what constitutes modern interpretation

often says more about the critic and his or her social circumstance than it

does about the text itself. Two examples will suffice. Both use only the

film as text. Writing in the 1970s, Phillip Zito, then editor of The

American Film Institute Catalog, described Topsy and Eva as "the most

extreme and racist of the silent films preserved by the AFI." Although he

ascribed the role to the wrong sister, Zito branded the performance as "one

of the most damning examples of racist portraiture in American film." Topsy,

as he saw her, was "ignorant, thieving, superstitious, undisciplined, given

over to swearing and biting; she eats bugs picked from flowers and butts

heads with a goat. And she is dirty . . ." For Zito, the film was "about a

black character redeemed by becoming white in all things except color. And

color was the one thing that will never wash away."

In a recent article for The Drama Review entitled "Uncle Tom's Cabin: Before

and After the Jim Crow Era," Michele Wallace assigned another, and quite

different, meaning to the film. Wallace asserted at the outset that "she

chose not to study" silent film but rather "it chose me through the natural

inclination of the depressive to always choose that which will reinforce and

consolidate her negative self-assessment and her pessimistic mental state."

Perhaps because of her mind-set. she read Topsy and Eva quite differently

than Zito. For her the film was "wonderful." "The plot," she contended,

takes "bizarre comic liberties with Stowe's scenario and Topsy and Eva

become all but lovers." Wallace's Topsy is "heroic, adventurous and an

absolutely delightful trickster-figure." "In a nutshell," she concluded,

"the story here is not about the love affair between Uncle Tom and Little

Eva, which James Baldwin and other male commentators directed our attention

to, but rather the love affair between Topsy and Little Eva." |

|

The contradictions evident

in these two readings of the stabilist version of the text cry out for

simpler explanations of the totality of the Duncans' work as Topsy and Eva.

It is tempting to see Topsy and Eva, in all its variants, in terms of race,

gender and class. Doing so, however current it may be, misses more basic,

and perhaps more meaningful, areas of exploration. Just how did Topsy and

Eva manage to survive in a rapidly changing media environment? What allowed

for public acceptance of Stowe's novel as a musical comedy? Why is Rosetta

Duncan, hailed as a, if not the, premier comedienne in her own time, now

neglected, if not forgotten?

The Duncans indeed were

prescient when, after a string of successes in vaudeville and in variety

shows, they sought another medium to display their talents.

Both vaudeville and |

| |

|

| |

Sweet Onion Time |

|

|

the variety show would soon

be dying industries. True vaudeville was alive and well until near the end

of the Twenties, but by early in the decade it was already threatened by

silent film. The talkies would put it to rest. By 1923, the Duncans knew

that the variety show might well die with vaudeville. While the Follies and

scaled down and more sophisticated variants of variety lasted longer than

vaudeville, the genre soon would become the property of the movie industry.

The popular Big Broadcast series of films in the Thirties is telling both in

its title and in its appropriation of the form.

The Duncans had the right

idea, and they were ahead of their time, when they explored both musical

comedy and film as more modern venues for their talents. Of course, what

they ended up doing was vaudeville dressed as musical comedy. As a musical,

Topsy and Eva would never be mistaken for Showboat. Their failure in film, a

medium they explored several times, is most marked by their last movie as a

team. It's A Great Life, produced in 1929, was a thinly veiled version of

their own life presented in a saturated market of back stage comedy-dramas.

Ironically, in that same year The Broadway Melody became the first

all-talking, all singing and dancing film to win the Academy Award for Best

Picture. Bessie Love and Anita Page were cast in the roles the Duncans

sought. Bessie Love, in what would have been Rosetta's role, paid homage of

a sort to the team. When her stage sister, Anita Page, expressed concern

about making it on the New York stage, Love responded: "What did the Duncans

have when they hit Times Square?" She then reminded her sister that they had

outplayed the Duncans on the vaudeville circuit anyway. The Duncans had the

right idea, they just could not cross the boundaries of the new media with

any success. They were destined to continue to be Topsy and Eva.

The Long Run |

|

|

|

Photo. of the Duncans

Enterting the Troops

Fort Ord, California (1942)

THE HAND-WRITTEN CAPTION ON THE BACK READS:

"The Famous Duncan Sisters|Better Known As "Topsy and Eva"

in "Uncle Tom's Cabin" |

|

|

Despite their inability to

successfully cross mediums, the Duncans managed to keep Topsy and Eva before

the public in one form or the other for three decades. Just what made the

Duncan's Topsy and Eva so popular for so long? Edward Wagenknecht believes

that "the Duncan Sisters gathered the last great Uncle Tom harvest because

they had the wit to see that theatrical taste had not changed so much as

smart people supposed . . ." "All that was needed to give Topsy and Eva a

new lease on life," he claimed, "was to give it a modern veneer." That

constantly changing veneer took an already corrupted version of Stowe's

novel and made it the original story. For the show to work, enough of

Stowe's novel had to exist in the public memory to provide a backdrop for

the performance. Enough of it had to be forgotten for comedy to work. Not

once did a reviewer, in pointing out the obvious differences between the

musical and the novel, make a point about what the show did to Stowe's

message beyond the obvious toying with the text. In a decade in which the

KKK would rise again, lynchings would haunt the country and the NAACP would

be formed, Topsy and Eva seemed to sit outside the politics of the Twenties.

It would remain |

|

so for thirty more years.

Audiences with at best vicarious experiences with the real world of slavery

seemed to be able to dismiss Stowe's moral as irrelevant. In a sense,

nostalgia had a longer shelf life than moral protest. The modernized tale

offered a happier past, one in which Eva would not die and Topsy would best

Legree and all he stood for.

As the Duncans continuously

updated their version of the tale with songs to fit the times, the show

moved further from the past in which it was set. Topsy and Eva could fit "Ukelele

Lady" and "The Mean Cicero Blues" into the act and make them work. Rosetta's

skill with the ad-lib most likely kept the show up to date night after

night. On the vaudeville stage the Duncans would mix hits from the show

while taking Topsy far beyond Stowe's world. Topsy singing in German, for

example, may have freed her from the world of the novel. It also may have

made Rosetta and Topsy one and the same.

What is one to make of Rosetta Duncan and the Topsy she created? In her time

she was a comedienne of the highest order. Compared by some to Charlie

Chaplin and to Al Jolson by others, she was "a blackface artist without

equal." "The show is all Topsy," a Los Angeles reporter claimed when the

performance made its third trip to that city: "Topsy hiding under Miss

Ophelia's billowing hoop skirt, Topsy bringing Eva out of faints . . . Topsy

wagging her toes at the orchestra leader, and Topsy just plain making

faces." During the World's Fair run in Chicago, Carol Frink of The Examiner

described Rosetta's work "as funny as Ed Wynn, Eddie Cantor, Jack Pearl and

all four Marx Bros. A masterpiece of comic acting." "Topsy holds her

audience breathless and curls them around her little finger with an ease

which not one performer in a million achieves," one observer reported.

Critic after critic marvelled at Rosetta as an ad-libber.

As the creative focus behind the shows pratfalls, Rosetta knew how to adapt

the work to place and time. Typically, Charles Collins of The Chicago

Tribune, who reviewed the 1933-34 version of the play, pointed out that

"along the musical front, everything is fresh fodder for the jazz band and

the radio warblers." "Rosetta's fantastic interpretation of the role of

Topsy displays modern comic improvements," he noted. "With her gift for sly

roguishness she has built the part with wisecracks and grotesque by play.

This is a Topsy developed to meet the current taste by the Olsen and Johnson

method." |

|

The Duncans were able to

adapt Topsy and Eva, but they could not escape the roles. Cork had become

Rosetta's life. As early as 1926, a Denver reporter claimed that "blacking

up for two years has had a psychological effect on Rosetta, and it has grown

into a regular idea." The Duncans now hoped "to do something for the

perpetuity of the pickaninny." Between scenes they began "working on the

score and story of a ballet -- a black-face ballet." "It is to be all

pickaninny," one explained, "and starts 'way back in the folklore days,

comes through plantation times up to the first ragtime, grazes around

syncopation and ends up with modern and joyful jazz." The idea was "to tell

the whole story of the Negro melody from beginning to end."

There would be no ballet, but Topsy

|

| |

|

| |

The Duncan Sisters MGM

Publicity Postcard (1929) |

|

|

|

trouped on in roles far

away from Stowe's novel. In April of 1935, for example, the sisters took

Topsy and Eva to Spain in a comedy sketch on Rudy Vallee's Fleischmann Hour

broadcast over WEAF. Imagine Topsy as a bull fighter!

Perhaps Rosetta Duncan was

too successful as Topsy for us to recall her work now. Clearly she never

escaped the role she established in her own time. One suspects that for

audiences Rosetta and Topsy were one in the same. She either could not, or

fame would not allow her to, develop new comic personas. Success as "the

best Topsy which the stage has seen in my time," as one critic put it, may

well have made Rosetta Duncan persona non grata in ours. Still, as the

signature song of Topsy and Eva suggests, the Duncans are well worth

"Remembering." |

| |

Credits &

Acknowledgements:

Our thanks to John Sullivan the

author for the use of the article on the Duncan Sisters:

©

Author John Sullivan, University

of Virginia - Website;

Uncle Tom's Cabin

Some Pictures Courtesy the

Harvard Theatre Collection, The Houghton Library; From The World's

Greatest Hit, by Harry Birdoff (Vanni, 1947); ALL OTHERS. From the

collection of the author.

If you have

any information on the Duncan Sisters Please contact the author via 'Uncle

Tom's Cabin' |

|

|

|