|

|

|

|

|

|

Ketchikan, Alaska - Nearly 120 years ago today, an American coastal steamer pulled into Port Chester on the west side of Annette Island. On board the "Ancon" was the federal commissioner of education Nathaniel H.R. Dawson who was on a tour of educational facilities in the territory. |

|

But that was not why the Ancon anchored off Annette Island on Aug. 7, 1887. Also on board the ship was Father William Duncan. Duncan - an Anglican missionary who has spent 30 years in British Columbia - was meeting with an advance party of more than 40 Tsimpshians from Old Metlakatla near modern day Prince Rupert, B.C.. Duncan was returning from Washington, D.C. where he had obtained permission from the US government to move more than 800 Tsimpshians to Alaska. This was the second time that Duncan tried to set up a Native society that was separate from the temptations of modern white society. Duncan had arrived in Port Simpson, just south of the Russian Alaska/British border in 1856 and quickly discovered the problems facing the native Tsimpshian as the white presence increased on the North Coast. In 1862, the new settlement of Metlakatla was established 20 miles south of Port Simpson but within two decades Duncan and his community had become a thorn in the side of his church hierarchy and the secular leaders in the British Columbia government. |

|

|

"Duncan was a lay minister with the Church of England and a man of great principles," according to information provided by Community Secretary Ellen Ryan to the US military in 2004. "He disagreed with the church authorities in Old Metlakatla over teaching certain rituals and ceremonies to the Tsimpshian Indians. This disagreement led to the church seizing Tsimpshian lands, and almost led to open conflict." Duncan journeyed to Boston and then on to Washington, D.C. where he met US President Grover Cleveland, who was sympathetic to the plight of the Tsimpshian Indians, according to Ryan's "History of the Metlakatla Indian Community." Ryan wrote that Cleveland recognized the right of the Tsimpshian to occupy land within their native home region regardless of the division of the area by Canada and the United States. He told Duncan to select an island in Southeast Alaska for the community's new home. |

|

Tsimpshian Chief Daniel Neashkumacken then responded to Dawson's speech. "The God of Heaven is looking at our doings here today," Chief Neashkumacken spoke in Tsimpshian which was then translated by Duncan. "You have stretched your hands out to the Tsimpshians. Your act is a Christian act. We have long been knocking at the door of another government for justice, but that door has been closed to us. You have risen up and opened the door to us, and bid us welcome to this beautiful island, upon which we have take refuge from our enemies, and where we have decided to build our homes. What can our hearts say to this, except that we are thankful and happy." |

|

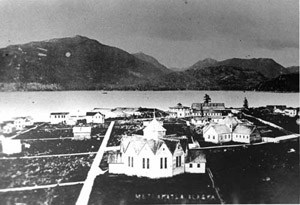

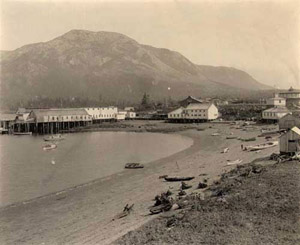

"The first flotilla of 50 canoes left almost at once," Murray wrote. "Over the next ten days boats of every shape and size ferried the natives and their possessions across the 70 mile stretch of water, some of it open Pacific. Six separate fleets, each comprising from 30 to 70 craft, including canoes, fish boats, scows and rafts made the voyage. They carried 800 men, women and children and assorted belongings." Two small steamships also carried supplies from Old Metlakatla to the new one. Approximately 100 residents of the old community stayed behind. Duncan quickly drew up plans for the new community with roads, public buildings, a school and the largest church in the territory of Alaska. |

|

|

On April 28, 1889, a small church and school building was dedicated, which later became part of the island cannery. The larger church was built later and it was big enough to hold nearly the entire community. It burned down in 1949 and was replaced by the slightly smaller William Duncan Memorial Church, which remains the most prominent building in Metlakatla. In 1891, the Congress officially recognized the community and created the Annette Island Reserve as a federal Indian reservation. That gave the native title to the entire 86,000 acre island. In 1916, the federal government extended community control to the waters up to 3,000 feet out from the reservation. That control allowed Metlakatla to continue to use floating fish traps in its waters, even after the State of Alaska banned them in 1959. |

|

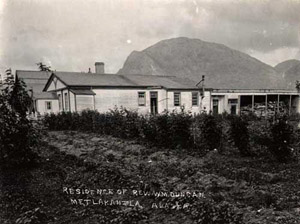

In 1918, Father Duncan died and his community carried on without him. Duncan's Cottage, built in 1891, is now a museum and one of the community's main tourism attractions. The community also operated a cannery and also an active boat building business that supplied many trolling and seine boats for the growing Ketchikan salmon industry. The next big economic boost for Metlakatla was World War II. |

|

"The island held a crucial, albeit small (and now almost forgotten), position in the defense of Alaska during the Second World War," wrote Canadian historian Murray Lundberg in "Annette Island, Alaska in World War II" on his Explore North website. " As the United States made ever-quicker preparations for the possibility of war from 1939 through the fall of 1941, traffic through ports on the Pacific coast became extremely heavy. At Seattle, in particular, facilities were stretched to their limits, and the American forces began discussions with Canada for using Canadian ports for shipment of troops and materials to Alaska. The port of Prince Rupert was deemed to be especially important, but Canada's ability to defend it against attack was very limited, with only a seaplane base." |

|

|

The airfield on Annette had begun in 1939 as a Civilian Conservation Corps project, according to Lundberg, but as the war in Europe expanded, it was put on a fast track. |

|

"Work was continued on the field through the winter of 1941-1942 by the Army Corps of Engineers," Lundberg wrote "Canada offered to supply a squadron of fighters to Annette, and by May 5, 1942, No. 115 (Fighter) Squadron was in place, becoming the first Canadian force ever based in U.S. territory to directly assist in American defense." Shortly after the base and its 10,000 foot runway became operational in the summer of 1942, the Japanese attacked Dutch Harbor and invaded Attu and Kiska islands in the Aleutians. "On July 10, 1942, a report stated that a Japanese submarine had been sunk the previous night off the coast of Annette Island by several aircraft and the Coast Guard cutter McLane," Lundberg wrote. "Air traffic at the Annette base became quite heavy at times, with C-47s, Cansos, Bolingbrokes, Norsemen, P-40s and even the odd Hurricane appearing." |

|

Activity in Metlakatla from the wartime airfield continued to be brisk through 1945. After the war, the airfield reverted to the control of the Civil Aeronautics Board (the forerunner of the Federal Aviation Administration). As the only large airfield in the region, it served as a hub as air transportation gradually grew to supplant water-borne transportation in the region. At the same time, Metlakatla officials first began prompting the federal government to build a road from Metlakatla to the northeast part of the island. The idea was that the new road could hook up with a shuttle ferry and improve access to Ketchikan, fifteen miles to the north. It would be nearly 60 years before the road construction would start. The airport continued to operate until Ketchikan's Gravina Island airport was completed in 1973. The US Coast Guard kept its Southeast search and rescue wing on Annette until consolidating operations in Sitka in 1977. The only operations that currently take place at the airport are National Weather Service ones. |

|

|

|

William

Duncan's Christian Church Choir, 1909 |

|

In 1971, when the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act was being considered. Metlakatla was asked if it wanted to end its reservation status. The settlement act would have provided land and payments to the community members, but Metlakatla chose to remain a reservation and is the only reservation in the state. The next economic boost for Metlakatla came when Louisiana Pacific built a sawmill in the early 1980s that operated - off and on - until 1998. The closure of the Annette Island Hemlock Mill - the community's largest employer - and reductions at the Annette Island Packing Company because of industry wide cutbacks due to competition from farmed fish have hurt the community's economy in recent years. The Bureau of Indian Affairs estimates that unemployment rates have topped 80 percent at times in the community. |

|

In recent years, the Metlakatla Indian Community has seen an increase in tourism opportunities either through private tour operators or the visits on the Alaska Marine Highway System which has gone from semi weekly to daily service with the MV Lituya in the last two years. With the military continuing to work on the Walden Point road, scheduled for completion in 2007, ferry service to the island from a Saxman terminal south of Ketchikan will be even more frequent. Community members were also cheered when a bottled water plant opened in 2003 and began marketing Purple Mountain water to the region and elsewhere. |

|

|

One of Duncan's most controversial edicts was that Metlakatla Tsimpshians were to give up many of the native traditions as they "assimilated" into the larger Canadian and then American cultures. Modern Tsimpshian artist/carver Robert Hewson said - on a Metlatkla artists' website - that when he was growing up he had to go to Ketchikan to see traditional native arts because nothing was being produced in Metlakatla in the 1950s. "When the Tsimpshian moved away from Old Metlakatla to their new home in Alaska, Duncan told them that he had given up his old ways to go to Alaska, and that they should do likewise," Hewson wrote. " As symbols of their old ways, they should destroy their masks and rattles, headdresses and robes. On the beach, the Tsimpshian built a huge bonfire and burned thousands of precious objects, many that had been handed down for generations. After that there would be little public display of tribal art for many, many years." |

|

One of the Tsimpshian artists who carried on, Hewson said, was Casper Mather who had been 11 years old when the community moved from Canada to the United States. Mather moved to Ketchikan in the early 1920s and continued to make small carvings and totems that he sold to visitors who arrived on the steamships and later the early cruise ships. Mather continued to sell his art to the visitors up until his death in 1972 at the age of 95. "He did the roughest carving you could imagine, but it had a power that I could feel.," Hewson said about Mather. " I wondered if I could do that too." Another carver who stayed in Metlakatla was Eli Tait. Tait - like Mather - also confined his work to smaller totems and other works primarily for the tourism trade. Tait was one of the four residents who chose the new townsite and also served as an early mayor. He outlived Duncan, dying in his workshop in 1949 at the age of 77. Sydney Campbell was one of the few carvers from Metlakatla who continued to carve full size totem poles. Campbell was nearly 40 years old when Duncan's followers moved to Alaska. He also carved numerous smaller totems for the tourist trade but also carved two full size totems that were outside the Knox Brothers curio store in Ketchikan for many years in the early part of the 20th Century. Campbell died at age 94 in 1926 and was eulogized in the Ketchikan Chronicle as an "excellent boat builder as well as a good carpenter and carver." |

|

In 2003, Tshimpshian studies was made an official part of the Metlakatla School District curriculum because of the efforts of local resident Mque'l Askren. But even more than 85 years after the death of Duncan, Askren says, there was still some community concern about teaching traditional Tsimpshian culture in the classroom. "No matter what our personal beliefs about the missionary, it's part of our history," Askren told Indian Country Today in 2003. Askren told Indian Country Today that she didn't blame the town's seniors for being unaware of their culture because many were taught in government schools and weren't exposed to their culture and history. "I'm too young to think about the culture and it should only be the elders," Askren mentioned about what's been said about her. "But the elders are holding me up saying 'Keep doing what you're doing'." Although Duncan's legacy is controversial in the modern world, the 1,500 Metlakatla residents continue to celebrate Founder's Day each August 7th in honor of the creation of their homeland. |

|

Credits & Acknowledgements:

1.

Picture - William Duncan sitting by his

fireplace Donor: William W. Jorgenson, Tongass

Historical Society 81.9.3.2 Photograph

courtesy Ketchikan Museums

Stories

in the News - Ketchikan, Alaska; Author - Dave

Kiffer, a freelance writer living in

Ketchikan, Alaska. Contact Dave at

dave@sitnews.us |

|