|

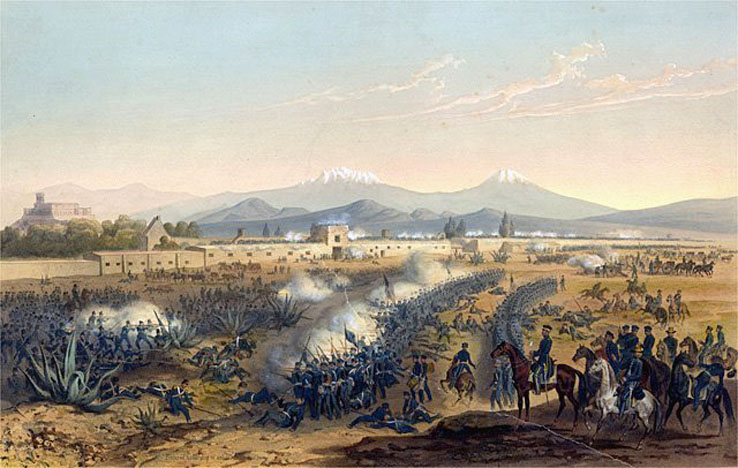

Churubusco is an Aztec word

meaning "place of the war god." It was appropriately named. Here the

infantry faced well entrenched and fortified Mexican troops, including the

renegade "San Patricio Battalion." Duncan pushed his guns out in front of

the infantry, in what had by then become a standard tactic, in an attempt to

blow a path through the enemy formation for the U.S. infantry to pass so

they could "roll up" the Mexicans’ flanks. At 200 yards Duncan's cannons

pounded the Convent of San Mateo and its defenders (the pockmarks are still

visible on the eastern wall of the convent/fortress). Finally the defenders,

seeing they were cut off', surrendered. August 20, 1847, marked the day

Santa Anna lost two battles (Contreras and Churubusco), and lost a third of

his effective troops to defeat, desertion, capture, and casualty. The road

to the outskirts of Mexico was open.

As the American army moved toward the City of Mexico, Santa Anna had floated

rumors that he had been using the old Molino del Rey (King's mill) to

foundry cannon. Scott rose to the bait and attacked. The approach to the

Molino was guarded by a supposedly minor redoubt, the Casa de Mata, about

500 yards west of the Molino and covering the main approach to it and the

castle of Chapultepec. Duncan positioned his battery and fired on this

obstacle. The American infantry was thrown back several times suffering

heavy losses in the process. Both the Casa de Mata and Molino del Rey

eventually fell. Afterward, there was no evidence of the Molino ever having

been used as a foundry and Scott withdrew his forces from the fruits of this

hard won victory. A dispute subsequently broke out between Scott, Worth, and

Pillow as to the effectiveness of the preparatory bombardment on the Molino

and Casa de Mata. Duncan, as Worth's artillery officer, was in the middle of

the argument. This dispute, however, merely presaged the one which would

erupt between the principals after the fall of Mexico City.

At 8:00 am on September 13, 1847, the Americans stepped off against

Chapultepec. Henry Jackson Hunt, Duncan's 1st Lieutenant, pushed a section

of Battery A (comprised of a 6 pdr. gun and a 12 pdr. howitzer) to the front

of the ramparts of the capitol city. Every man and horse was hit as they

unlimbered, Hunt being wounded three times himself. Muzzle to muzzle with an

enemy cannon in an embrasure, Hunt fired first and blew the Mexican cannon

and its crew away. Down the causeway to the Garita (gate) de San Cosme Hunt

pushed his two guns. Fifty yards at a time Hunt leapfrogged his cannon until

a lodgement was secured.

On September 14, 1847, Santa Anna surrendered the city. Scott entered in

triumph, dressed in a grand manner befitting "old fuss and feathers." Worth,

Scott, and Pillow again fell to arguing with Scott over responsibility for

the attacks, losses, and retreat at Casa de Mata and Molino del Rey. A

letter reputedly written by Duncan critical of Scott was published in a

Pittsburgh, PA, newspaper. Scott had Pillow, Worth, and Duncan brought under

inquiry. Charges and countercharges flew back and forth between Mexico and

Washington, DC. There were several letters written on this and other

subjects, and the authorship of several of them remain obscure today. The

affair dragged on for some time but President Polk, who did not like the

imperious Scott and suspected him of being at least in part motivated by

presidential ambitions, eventually let the matter drop. The only real

outcome of the subsequent inquiries was that Scott was eventually replaced

as the Army commander.

In January, 1849, Colonel Croghan, who had been the Inspector General of the

Army, died. President Polk rewarded Duncan by naming him to the post. While

on an inspection trip to Mobile, Alabama, that summer, however, Duncan

contracted the vomito he had successfully avoided In Mexico and succumbed on

July 3, 1849. Ironically, Duncan's remains joined that of his former

commander, General Worth, and another artilleryman, Major Gates, both of

whom had also died recently, in a funeral cortege through New York City.

Duncan was buried in his home town and later reentered just across the

Hudson River at the United States Military Academy at West Point. His

eulogizer characterized Duncan's career as like a "meteor, not only in

brilliancy but duration."

Artillery emerged as the greatest power on the battlefield in America’s

first foreign war. Light artillery companies continually fought from exposed

positions, firing rapidly, changing positions quickly, and concentrating

their fire on selected targets. Except for the exposed position part, the

same principles have been employed from then on down through Desert Storm.

Mexican artillerymen, even though they had comparable equipment, could not

match the American's mobility and training. Mexican artillery still depended

on mules and oxen to pull their guns, and on civilian teamsters to man the

transport. American artillery units frequently split into sections,

generally two gun increments, to counterattack on separate parts of the

battlefield, only to merge again later to repel massed Mexican infantry

attacks with canister, shot, and shell on yet another part of the

battlefield. John Eisenhower in his book So Far From God stated that,

"...the field artillery made the difference between victory and defeat for

the Americans."

Duncan emerged from the war as the premier American artillerist, due in part

to the fact that he survived it, but also due to his intrepidity and

inspirational leadership. Duncan's guns were frequently well in front of the

infantry in exposed positions, attempting to secure lodgement for them.

Henry Jackson Hunt was Duncan's friend and pupil and took command of the

battery after Duncan's departure. Other renown future commanders of Battery

A, 2nd U.S. Artillery included John C. Tidball (who was the first to have

"Taps" played at a funeral on the peninsula in 1862), Alexander Pennington,

and John H. Calef, who commanded the battery at Gettysburg.

During the 1850s the Army and its artillery was once more downsized. Company

A and five of sister batteries were dehorsed by Secretary Conrad in 1852.

The next year saw Hunt on the way to Ft. Washita, Indian Territory, to mount

Company M and act as an instructional unit--two other companies having been

given a similar duty. He had left Company A in 1852 and was now in command

of Company M, 2 nd U.S. Artillery. When Hunt arrived at Ft. Washita he found

the 11 year old fort in a state of near ruin. The roofs were dilapidated and

leaky, the hospital unfit for use, the stables "insufficient and unsuitable

for the accommodation of artillery horses," the storehouses unfit, and the

magazine located in an unsafe position. It lacked, in addition, no granary,

workshops, or gunhouse. Hunt set about correcting these deficiencies. During

his stay there he had the company of several notable officers who were

either temporarily assigned to the post or visited there: Robert E. Lee,

Braxton Bragg (who resigned the Army in disgust when Company C, 3rd U.S,

Ringgold’s old battery, was again dehorsed), Joseph E. Johnson, and William

Barry.

Hunt went on to command the artillery for the Army of the Potomac. He

established procedures for the logistics and supply of the artillery which

is in large part still in use. In fact, some letters to the FA Journal

(official publication of the U.S. Field Artillery Association) after Desert

Storm commented that if the lessons that Hunt and others had taught the Army

in the Civil War had been remembered the conflict might have been "easier,"

if not shorter. The tactics and procedures laid down by nineteenth century

artillerists such as Ringgold, Duncan, Bragg, and Hunt live on in this

regard.

Click Here for more Information on

Col. James Duncan |